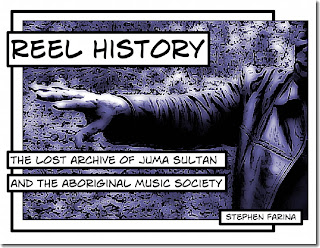

Over the past two years, I've been working as the editor for Music:Interview, a new series from Wesleyan University Press featuring books that creatively anthologize "the most provocative and resonant interviews by a significant figure in music." A project in the series I'm particularly excited about is Stephen Farina's Reel History: The Lost Archive of Juma Sultan and the Aboriginal Music Society. While the book introduces musician Juma Sultan and his performances with the Aboriginal Music Society from the 1960s and ‘70s, it is also an exciting experiment in form. It dynamically combines oral history, the graphic novel, audio recording, and film to narrate the story of Farina's own encounters with Juma Sultan and to make sense of Sultan's decaying but extraordinary archive of historical reel-to-reel tapes, 16 mm films, and posters from the heyday of black nationalist politics and avant garde jazz. Reel History is Wesleyan's first "digital-born" book--that is, it is available an e-book only--reading it was a new experience for me, since it invites a range of readerly engagement. One moment you are following Farina's story-telling in words, the next you encounter a visual montage (sequential panels evoking Sultan's body movements as he reminisces and laughs). Along the way, you can click on links that play clips of the music being discussed, or you can watch a silent movie of the AMS rehearsing. It is truly a book illustrated for readers in a digital age, used to moving between text, video, and audio with ease.

Coincidentally, I've been reading another older work, for a class I'm about to teach on social justice and the New Deal, that also experimented with illustration and narrative, albeit in a very different way: Lynd Ward's Vertigo. Ward was a printmaker who combined wood engraving and a strong commitment to social justice to create a series of "novels without words" in the 1930s. I had never heard of Lynd Ward until he was recommended to me by a friend, but his work is extraordinary, representing a kind of moving picture, with the "movement" created not by visual illusion or mechanical device--or even a layout of frames, typical of comics and graphic novels--but rather by a reader's own engagement with narrative flow. Each page holds one illustration, exquisitely-rendered: establishing scenes of city streets, characters in various settings, conversations, dreams, close-ups of faces and expressions. When taken together in sequence, they tell a complex story. In an earlier work, Wild Pilgrimage, Ward interestingly used different colors--red to indicate interior thought and black to indicate exterior action; in Vertigo, he dispensed with such cues, putting everything into the composition and sequence of the images. Sometimes, you don't know what's going on for several pages, but then with one expression or twist, it all becomes clear.

Finally, thanks to Andrew Sullivan's blog at the Daily Beast, I was made aware that the Folio Society is re-publishing William Faulkner's The Sound and the Fury (1929) in the way that Faulkner originally intended, with different colored text indicating different time periods. The Sound and the Fury is a complex, layered book, with the same story told from multiple points of view and with abrupt shifts in narrative style and time period. Faulkner had originally hoped to use colored ink to help readers negotiate these shifts, but the publisher refused, so he had to rely on roman and italic type instead. Now, we can experience the book graphically in ways we could not in the original Random House editions.

I've been reading a lot about reading lately, but I have not come across scholarship that addresses the processes of reading a graphic text in the way that, say, Wolfgang Iser or Stanley Fish have addressed the more conventional word text, or art historians have made sense of looking at a painting. I'm fairly certain that this is due only to my ignorance, so I'd appreciate any recommendations for such criticism and theory in the comments. In the meantime, happy "reading," whatever that entails.