Sunday, May 29, 2011

What Song Are You Listening To?

This video by filmmaker Tyler Cullen looks to me like the start of a new Music in Daily Life Project for the iPod generation. It also does a bit of what I had missed in Nikil Saval's n+1 article on the social meanings of the iPod.

Thanks to Kottke.org for flagging it.

Saturday, May 28, 2011

Fans Celebrating After a Win

The Bruins won the playoffs last night; they haven't been in the running for the Stanley Cup since 1990. This morning, the Boston Globe released a video of fans celebrating. In many ways, it reminds me of a much older documentary, Heavy Metal Parking Lot, where fans, before a Judas Priest concert, gesture about their love of the band (and other bands) in front of the camera.

While there is definitely something about the camera that makes people act exaggeratedly, I also see the ways in which fans are continually extending the frame of performance outward in all directions: before and after the game, and beyond the seating area of the event, into the hallways leading out of the arena, into the parking lot, and even into the streets. Screaming one's excitement is one thing during a game or concert; it is quite another in the spaces of everyday life.

The historian in me longs for a motion picture of fans in 1900 doing this. Perhaps there's an early Edison short?

While there is definitely something about the camera that makes people act exaggeratedly, I also see the ways in which fans are continually extending the frame of performance outward in all directions: before and after the game, and beyond the seating area of the event, into the hallways leading out of the arena, into the parking lot, and even into the streets. Screaming one's excitement is one thing during a game or concert; it is quite another in the spaces of everyday life.

The historian in me longs for a motion picture of fans in 1900 doing this. Perhaps there's an early Edison short?

Monday, May 23, 2011

Friday, May 20, 2011

Storefront News

On March 19th, I featured this photo of a crowd watching a scoreboard for the 1911 World Series, but I did not have a second photo that allowed me to show what, exactly, they were watching.

I'm all for the power of the imagination, but today Chris Marstall, at the Boston Globe blog, beta.boston, shared a series of photos, from the 1912 World Series (between the Red Sox and the New York Giants) that fills that gap. There is a similar crowd shot but also another image that shows the Globe's storefront blackboard (see below, in the upper left) on which staff members are posting scores.

I'm all for the power of the imagination, but today Chris Marstall, at the Boston Globe blog, beta.boston, shared a series of photos, from the 1912 World Series (between the Red Sox and the New York Giants) that fills that gap. There is a similar crowd shot but also another image that shows the Globe's storefront blackboard (see below, in the upper left) on which staff members are posting scores.

I would highly recommend Marstall's full post. I'm particularly fascinated by the shots of crowds, standing together on the sidewalk, getting the latest news. These days the news is so niche-marketed and individually-tailored, that it's difficult to even imagine what it must have been like to have a shared sense of "being informed," of participating with others in a ritual process of waiting for the news to unfold. The last trace we have of that culture is the national news on television every night, I suppose. And soon it's just going to be Brian Williams and me.

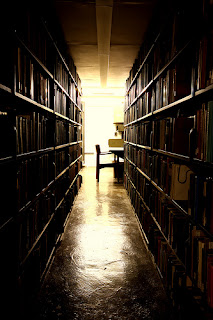

My Library Story

For those of you who work in or near university libraries, the “stacks,” or the shelves holding a library’s book collection, are probably rather familiar. But for the uninitiated, they can still have a wonderful power. I remember when I was a new undergraduate at Cornell University in the 1980s. Painfully shy and overwhelmed by the whole college experience, I was hesitant to ask any questions about anything, for fear of being discovered as the admissions mistake I sincerely believed myself to be. The one thing I had going for me, an avid reader, was that the place seemed to be very book-oriented. I learned with amazement, for instance, that Cornell didn’t just have one library, but at least seven or eight, each attached to a different school across campus.

In my first week as a freshman, I managed enough gumption to enter Cornell’s main library for undergraduate students, Uris. It was quite impressive for someone who had only previously experienced the local public library. Built in 1891 in Romanesque style, the main door was appropriately intimidating, opening up into a main reference and circulation room. The “Dean Room,” as it was called, was a large sun-splashed basilica, with its center filled with tables and study carrels and its walls lined with books and paintings of Cornell’s forefathers and illustrious donors. It was much as I had imagined an Ivy League school’s library would look like; there was a reverent hush about the whole place, and people seemed to be seriously engaged in scholarship. In fact, I thought that this room was the library. It was about the same size as my entire town library back home and, while it didn’t have quite as many popular novels, it more than made up for that with its complete sets of encyclopedias and authoritative-looking reference guides to every possible subject in human history. I figured that was what college libraries were supposed to be all about.

One day, while sitting in the Dean Room, I noticed a door to the left of the circulation desk. Every once in a while a person would disappear through the door and not return. This seemed a little odd to me; at first, I figured it was some kind of shortcut for staff only. But I decided to investigate. Maybe it was an alternative exit? Or maybe it connected to a study room of some kind? This was not easy for me to do. Remember that I dreaded being found-out as an imposter; my survival depended on looking like I fit in and not getting into trouble. (“You there! Where do you think you’re going?!” a librarian might have barked as soon as I approached the door. “Everyone here knows that door is off limits!” Then, with her eyes squinted in suspicion: “Wait a minute, why don’t you know that?....” And so on).

When I took a deep breath and went through, I found that it led to a set of stairs, stairs that went down underground. Each floor had a landing and a door—B, 2B, etc.--one of which I finally decided to open, as nonchalantly as possible, of course. When I walked through the doorway, however, I suddenly found myself unable to breathe, for extending out before me were rows and rows of bookshelves. They seemed to reach infinitely beyond me into a vast dimly-lit space that seemed to have been carved deep into the earth. And all of them held books of every size and color. There were thousands of books—maybe hundreds of thousands. I was awestruck and somewhat baffled. I had never in my life seen so many volumes in one place before. Was I supposed to be here? What were these books doing, here, rather than upstairs in the library? Had I stumbled on some kind of secret warehouse under the campus?

Then another student came in. He politely walked past me, turned on one of the timer-lights at the end of a shelf a few yards away, and started to search for a book whose call number he had scribbled on a piece of scrap paper. It dawned on me that there was much to learn.

A couple of years later, I gained access to the even larger graduate library at Cornell, and, as a scholarly researcher, I’ve since been able to explore some of our nation’s finest archives, including the Library of Congress (the stacks are off-limits, there). But I will still never forget that first moment when I stumbled on the actual book collection of Uris Library and discovered that the world was much, much bigger than I had ever anticipated. Oddly, perhaps, I still have a love not only for books but for rows of books. When you see photos of college libraries, there are usually interior shots that attempt to convey the majesty of an aisle in the stacks, with two rows of books converging at a distant point. But that’s only one piece of what can usually be apprehended—typically, there can be ten, or even twenty, aisles, extending across the breadth of one’s vision. And in bigger university libraries that happens on multiple floors. Together, the stacks of any library represent a mindbogglingly large ocean of books—of human knowledge—in which an earnest student might spend a lifetime exploring. And sitting in the stacks, literally immersed in print, is a kind of heaven on earth for some of us.

In my first week as a freshman, I managed enough gumption to enter Cornell’s main library for undergraduate students, Uris. It was quite impressive for someone who had only previously experienced the local public library. Built in 1891 in Romanesque style, the main door was appropriately intimidating, opening up into a main reference and circulation room. The “Dean Room,” as it was called, was a large sun-splashed basilica, with its center filled with tables and study carrels and its walls lined with books and paintings of Cornell’s forefathers and illustrious donors. It was much as I had imagined an Ivy League school’s library would look like; there was a reverent hush about the whole place, and people seemed to be seriously engaged in scholarship. In fact, I thought that this room was the library. It was about the same size as my entire town library back home and, while it didn’t have quite as many popular novels, it more than made up for that with its complete sets of encyclopedias and authoritative-looking reference guides to every possible subject in human history. I figured that was what college libraries were supposed to be all about.

|

| Dean Room, ca. 1900. Div. of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell U. Library |

When I took a deep breath and went through, I found that it led to a set of stairs, stairs that went down underground. Each floor had a landing and a door—B, 2B, etc.--one of which I finally decided to open, as nonchalantly as possible, of course. When I walked through the doorway, however, I suddenly found myself unable to breathe, for extending out before me were rows and rows of bookshelves. They seemed to reach infinitely beyond me into a vast dimly-lit space that seemed to have been carved deep into the earth. And all of them held books of every size and color. There were thousands of books—maybe hundreds of thousands. I was awestruck and somewhat baffled. I had never in my life seen so many volumes in one place before. Was I supposed to be here? What were these books doing, here, rather than upstairs in the library? Had I stumbled on some kind of secret warehouse under the campus?

Then another student came in. He politely walked past me, turned on one of the timer-lights at the end of a shelf a few yards away, and started to search for a book whose call number he had scribbled on a piece of scrap paper. It dawned on me that there was much to learn.

A couple of years later, I gained access to the even larger graduate library at Cornell, and, as a scholarly researcher, I’ve since been able to explore some of our nation’s finest archives, including the Library of Congress (the stacks are off-limits, there). But I will still never forget that first moment when I stumbled on the actual book collection of Uris Library and discovered that the world was much, much bigger than I had ever anticipated. Oddly, perhaps, I still have a love not only for books but for rows of books. When you see photos of college libraries, there are usually interior shots that attempt to convey the majesty of an aisle in the stacks, with two rows of books converging at a distant point. But that’s only one piece of what can usually be apprehended—typically, there can be ten, or even twenty, aisles, extending across the breadth of one’s vision. And in bigger university libraries that happens on multiple floors. Together, the stacks of any library represent a mindbogglingly large ocean of books—of human knowledge—in which an earnest student might spend a lifetime exploring. And sitting in the stacks, literally immersed in print, is a kind of heaven on earth for some of us.

|

| Uris Library Stacks, Photo by Eflon. |

Sunday, May 15, 2011

Saturday, May 14, 2011

Watching Jazz

An NPR Radio piece yesterday featured a fascinating new project, by musicians Jason Moran and Me'Shell Ndegeocello, to revive the dance music of Fats Waller. Moran and Ndegeocello talk about the ways in which jazz has moved away from its party-oriented entertainment origins in Waller's day. Moran explained, ""You know, the '20s [and] '30s, people dancing to music wasn't seen as bizarre or crazy. Now, if I play some Fats Waller music in a gig and someone starts dancing, they're the freak." Ndegeocello went further and noted something in jazz that she calls the "fishbowl complex": "You know, 'I'm going to come watch you.' I don't know how it got to be that way. It just has a specific historical reference now. And people forget that it started in brothels."

While Ndegeocello was likely referring to "jazz" with her pronoun "it," I heard the sentence as: "And people forget that [watching] started in brothels." I have no idea whether that is even historically accurate (when was the first brothel?), but the extent to which music served as a means for 20th-century prostitutes to display themselves before clients made me follow that mis-hearing a bit further and consider the framework of, say, a turn-of-the-century New Orleans brothel for understanding modern audiencing. Certainly a major theme in the history of audiencing in the United States has to be the development of the "gaze," with all the sexual, racial, political, and behavioral complexities involved in that action. We have created elaborate rules, buildings, institutions, technologies, and markets which explicitly support practices of exhibition and spectatorship and which often reinforce ideologies of social difference.

On the other hand, I'm a little hesitant about a broadly-applied "gaze" thesis in this case, because I do not agree that dancing to music is inherently better than witnessing music. Moran and Ndegeocello go so far as to oppose dancing to watching, implying that the former is active and participatory and will break down social barriers, while the latter is passive and distant, locking people into structures of inequality. Instead, I think there is a strong case to be made that playing, singing, watching, and dancing are all part of performance and have taken on various meanings (good and bad) in different social and historical contexts. It may be useful to encourage people to dance at jazz shows and revive the days of Fats Waller, but it might also be useful to remember why people stopped dancing at jazz shows in the first place. Namely, in the 1940s, bebop sidemen, distancing themselves from what they saw as an exploitive entertainment market and seeking a different kind of recognition in segregated America, sought to develop jazz in new, modernist directions. Their audiences--beats, bohemians, hipsters, students, and intellectuals--were motivated to participate as listeners in this new subculture of virtuosity, recognizing its avant-garde irreverence as a powerful reflection of their own rebellion against "middlebrow" America. In other words, in 1950, it made sense to some people not to dance.

Perhaps the more pertinent question in all this is why has the fishbowl model of jazz performance remained with us for so long? Why are contemporary jazz audiences reverently listening rather than exuberantly dancing? Waller's legacy depends on the answer to that question as much as it does on the impressive efforts of Moran and Ndegeocello to recover the bodily joy of his performances.

Sunday, May 8, 2011

Situation Room Photograph

While it does not depict a fan audience, last week's "situation room" photograph of President Obama and his advisors (by White House photographer Pete Sousa) is quite similar to some of the photographs of audiences that I have posted on this blog. I imagine, too, that it will become an historic and iconic image; certainly every new American history textbook is going to use it to summarize the 21st century's first decade.

Analyses of the photo have been appearing all this week; some of the better ones include Caleb Crain's discussion at Steamboats are Ruining Everything and Marco Bohr's Visual Culture Blog. While I won't add anything to their insights at this time, I hope that we can, in this moment, at least, acknowledge the significance of audiencing in our culture.

Update, May 9: Rabbi Jason Miller, via Andrew Sullivan's blog, reports that an Hasidic Jewish newspaper has removed the women in the above photograph. "Audience manipulation" is an old problem recognized by cultural studies scholars, but this is literal. Seriously, how does that change the tenor of the photo?

Friday, May 6, 2011

Mother, Owner, Fan

On this coming Mother's Day, we might pay tribute to one of the great mothers and fans in baseball, Helene Britton.

Britton's uncle, Stanley Robinson, along with Helene's father, Frank, were owners of a successful streetcar business in late 19th-century Cleveland. Their wealth enabled them to purchase the Cleveland Spiders in the the 1890s, which they then merged with the St. Louis Cardinals in 1900. On frequent family outings to ballparks in Cleveland and then St. Louis, they brought Helene along, who developed an enthusiasm for baseball, in addition to acquiring the more "refined" activities required of a woman of standing in the early twentieth century.

When her Uncle Stanley died in 1911, he shocked the world of baseball by leaving a controlling interest in the team to Helene, a 32-year-old mother of two, married to lawyer Schuyler Britton. Despite humiliating mockery from reporters and fans, she refused to sell her interest in the team. She brazenly attended all-male owners meetings and stood fast in the face of recalcitrant players, including her own team manager, whom she fired after mounting disagreements and an altercation in which he angrily said, "No woman can tell me how to run a ball game." And throughout her tenure as National League owner, she encouraged more women to take an interest in the game, moving Cardinals ticket sales from rough and male-dominated saloons to more respectable drugstores, arranging singing performances between innings, and, along with other clubs in the Midwest in 1917, eagerly instituting a "Ladies Day," when women, accompanied by a male escort, could get into the grandstands for free.

She finally sold the team in 1918, never losing her love for the game. She truly represented the will and determination of women--and mothers--in her day.

For a few more photos, see the Missouri History Museum's Flickr Exhibit. Useful biographies of Helene Britton can be found at http://bioproj.sabr.org/bioproj.cfm?a=v&v=l&pid=16895&bid=963 and http://baseballhistoryblog.com/tag/helene-britton/.

Wednesday, May 4, 2011

Storing All That Sheet Music

|

| Orchard House, Concord, Massachusetts: Dining Room. (The rack is on left). |

On a recent visit with my family to Orchard House, the home of Louisa May Alcott, I noticed a curious piece of furniture in the corner of the dining room that look a bit like an oversized dish-drying rack; it was a finely-finished platform, on bowed legs, topped with a frame intersected by large vertical slots. After the guide suggested that it might have held sheet music, I became curious about "sheet music furniture." Was there such a thing? How far did people go to organize their home sheet music collections in the 19th century?

This may seem like a bizarre topic to research, but in the age of the memory chip, we have a weakened understanding of the extent to which collecting music before the 21st century required a good deal of physical space and material organization. Besides the piano, one of the most successful consumer products for music in the 19th century was sheet music. (In fact, they often went together: getting a piano invariably meant starting a sheet music collection). Music publishers offered diverse forms of music, including lesson books for instrument and voice, souvenir versions of songs from the musical stage, hymns, minstrel songs, simplified versions of operas and symphonies. An enthusiast's sheet music could quickly number into hundreds of pieces, requiring some sort of cataloguing system for retrieval. As one writer lamented, "We so frequently go into homes and find sheet music thrown about in all sorts of confusion. One family has on old square piano and beneath it is a disorderly heap." (Locomotive Firemen's Magazine, October 1899, 420). How people dealt with issues of storage, organization, and display said a lot about how they consumed, valued, and understood music in general.

Many people paid to have their collections of sheet music bound in leather and personalized with their names embossed in gold on the covers. The binders purposefully indicated the individual preferences of their owners through variations in content and organization--by year, by style, by publisher, and by favorite pieces. they could be bulky, but when stored with other books in one's library shelf, they added a sense of refinement and personal achievement to the room.

Sunday, May 1, 2011

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)